Boleslaus Dalkowski

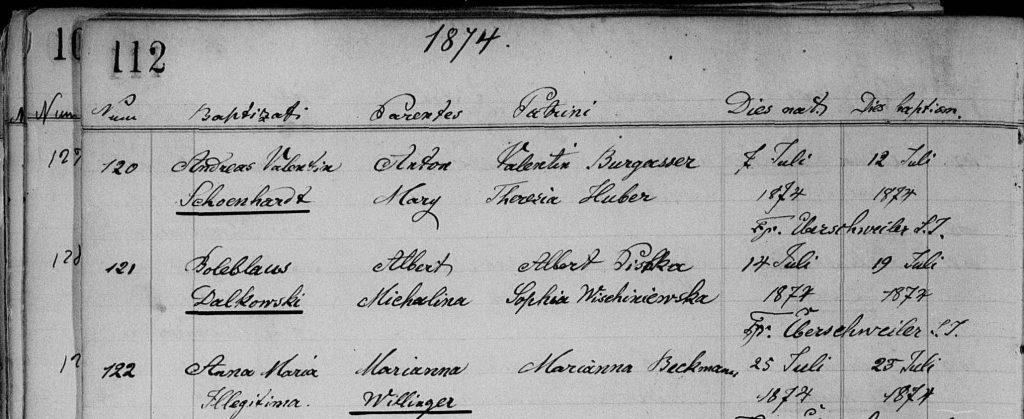

Boleslaus was born in Toledo to Adalbert and Michalina Pyszka on 14 July 1874 and baptized in St. Mary’s Parish on 19 July. He was one of two sons, the youngest, older brother was named Frank. The 1880 census shows the family living on Franklin Avenue.

His parents eventually settled in a home near St. Hedwig, next to Szelaszkiewicz Brothers’ Saloon at Dexter on Locust. When he was about 11 years old, the St. Hedwig riot occurred. His father, Adalbert, was killed in the riot. His mother, Michalina, re-married in 1887, to a man named Michael Brzeczka at St. Stanislaus in Cincinnati’s west side. Michael and Michalina returned to Toledo to reside there, first at 2736 Lagrange and later at 555 E. Park Street. Michael was a cabinet maker, and later a sheriff’s deputy, and seemed to have developed a good relationship with his step-sons. About 1889, when Boleslaus was 14, he went to Buffalo, NY to study the printing trade and later studied at St. Canisius College in Buffalo.

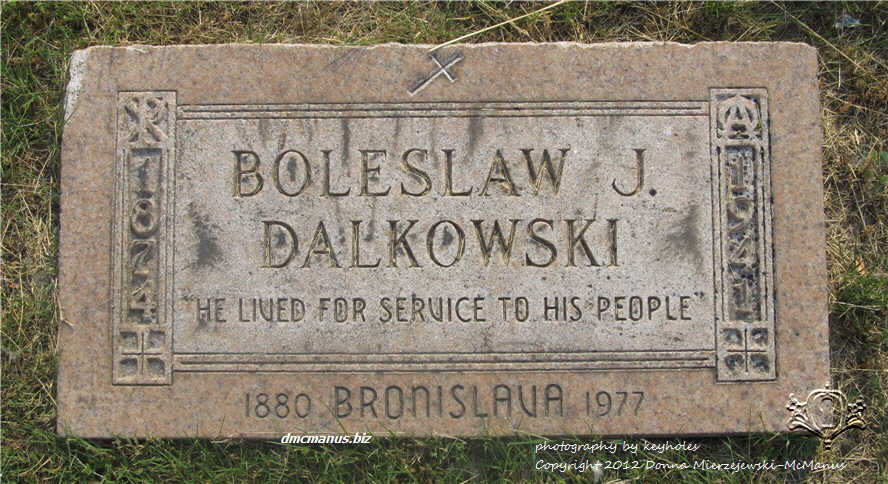

Boleslaus married Bronislawa Szwajkowski on 1 August 1899 in St. Hedwig, they would go on to have three children that I could locate: Theresa, Helen, and Edward.

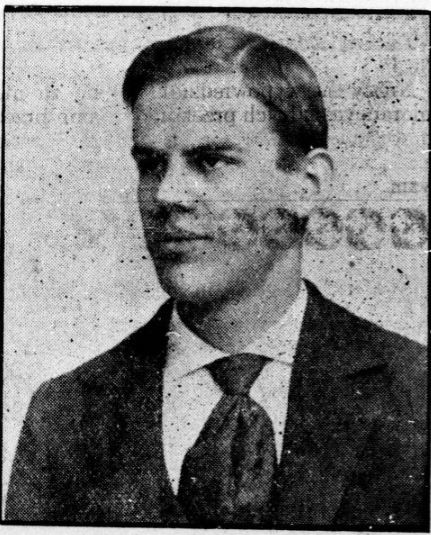

As a young man, one of Boleslaus’ first employers was the Ameryka Echo, run by A. A. Parynski. The paper was started around 1889, and published under several names–Ameryka w Toledo i Kuryer Clevanlandski, changed to simply Ameryka and ran under that masthead for about nine years from 1893 to 1902. From that point, the paper ran under the masthead Ameryka Echo until about 1971 when it was discontinued. Boleslaus would have been employed there sometime around 1894. His obituary, published in the Toledo Blade on 18 December 1941 states that he remained with the paper only a short period before publishing his own newspaper, a weekly Polish publication. He did have some success with his weekly newspaper but he accepted an offer to be a city editor for a Polish paper in MIlwaukee. He held that post for several months before returning to Toledo, where he joined the Toledo News and the Toledo Democrat, a paper that existed only about a month.

Boleslaw was mentioned in the paper initially on 1 June 1895, when Boleslaus was arrested resulting from a complaint by a Franciszek Krzeminski, president of Group 422 of the American Railway Union. Krzeminski claimed that Dalkowski transferred $106 of union funds to himself. Boleslaus’ employer was not mentioned; however the newspaper claimed that it supported a coal strike and a railroad strike in Chicago 1893 and then claimed the Dalkowski was “hired by capitalists to keep them informed of everything the Polish workers intended to do.”

Dalkowski claimed the $106 was for taxes, but the newspaper claimed he forged books and appropriated money. He then stated he wanted to “escape from the city.” Krzeminski heard this and he had applied for a warrant to arrest Dalkowski. Krzeminski seemed to have cut a deal in order to avoid Dalkowski going to prison for 3 to 10 years–the deal was the money would just be returned to the union. His family–brother Frank, step-father Michael Brzeczka, and his mother begged his forgiveness of Krzeminski.

The Ameryka seemed to be upset with this settlement–the Toledo Bee stated that the case was discontinued because Dalkowski was innocent and later, Ameryka claimed that Dalkowski stated the $106 was due to him as a secretary’s salary.

Ameryka then ran an article on 12 October 1901 when Boleslaus and his brother Frank both were running for local elected positions. The Ameryka claimed “Bolesław J. Dałkowski should not be elected to any office in the Union” and provided reasoning that Dalkowski was arrested for the embezzlement of $106 a few years prior, claimed that while he was a secretary for a union in Grand Rapids, that he did not deliver letters and newspapers unfavorable to him, and that along with his step-father, Michael Brzeczka, the ran a card agency and sometimes they keep the money before sending on. (A card agency is an organization that would transfer funds from one person to another over long distances.) There was a long list of reasons, but it was clear that the Ameryka did not care for Dalkowski. Ameryka had no trouble with attacking Brzezcka either. Michael Brzezcka was also known as “Majka Zabijok”, and Paryski published this criticism of him: “In the den of thieves, there is to be held an amateur performance fo Majka Zabijok. Aren’t these performances too many for these hard times?”

At the same time, his brother, Franciszek, was running for a similar office and Ameryka also refused to support Frank: “During the last election, he sold the votes of the Polish Republican party for $ 300, which covered all Poles with a terrible disgrace.”

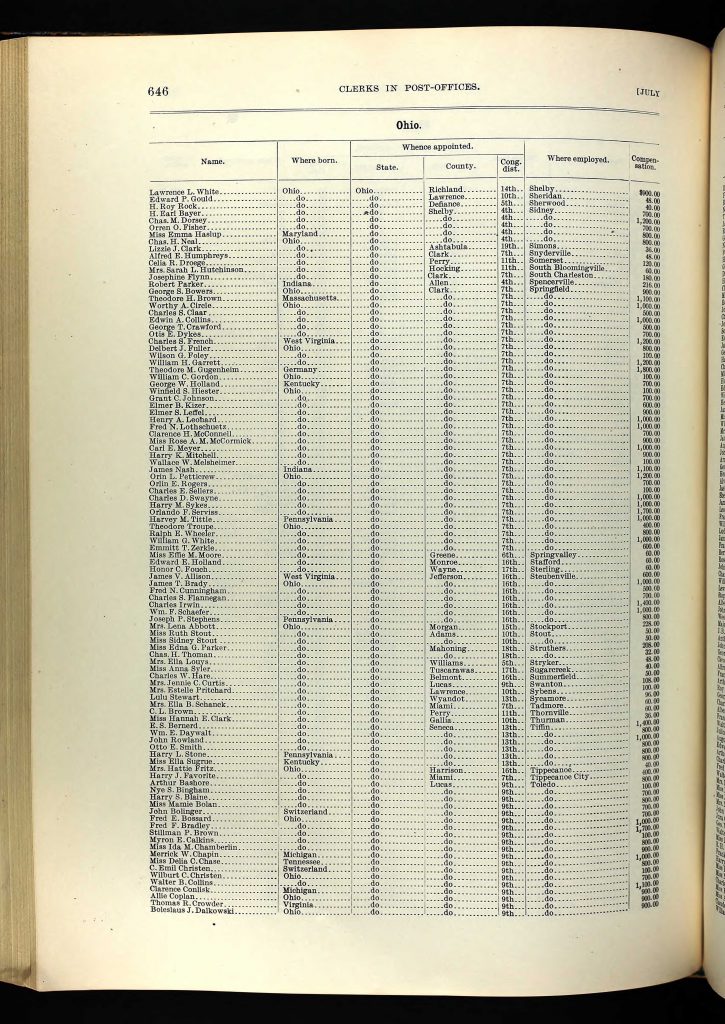

Sometime around 1902, Boleslaus began working for the US Post Office and managed an office in the 9th Congressional District. The Ameryka again started in on Boleslaus. 22 February 1902, they ran and article that claimed Dalkowski only purpose was to exploit Poles, that “we wrote more than once about Dalkowski’s cheating.”

The issue at this time seemed to be that as a post office clerk, Boleslaus received $15 from a Jacob Kaminski to send to a relative, Ignacy Koperski who was detained at Castle Garden while on his way from Poland. Ignacy was detained for lack of funds. It appears as if Dalkowski accepted $16.90 from Jacob Kaminski: $15 to send on to Ignacy and $1.90 “shipping fee.”

Ameryka then claimed that Jacob Kaminski, and his brother, Peter, both stated it was four days later Ignacy received the money, but it was only $10, and not the $15 promised to arrive via telegram.

Boleslaus then went on the offensive and wrote a letter to “Kuryer Polski” in Milwaukee, directed against the Kaminskis’ lawyer, Michael Lewandowski: “Antek (Dalkowski is referring to Antoni Paryski using this nickname)… I will go to the mayor of this city, Mr. Jones…. Boys want a drink? Because my Antek is funding…Aren’t you ashamed to talk so stupidly. You go drinking day after day and you stretch people.” (By stretching, Boleslaus means he believes Antoni Paryski stretches the truth.)

Items like this appeared in Ameryka or Ameryka Echo through the 1890s and 1900s. No real resolution to these two issues were published, that I know of or found. Given Boleslaus’ father’s role in the 1885 St. Hedwig riot and that he did have his own publication in Toledo for a short period after leaving Paryski’s organization, I have often wondered whether Paryski was assuming that Boleslaus was not a good person due to his father’s involvement with the St. Hedwig riot or felt he was a threatening competitor.

By the 1910s, it seems this squabbling died down, there are no mentions of disagreements about Boleslaus in the Ameryka Echo. Boleslaus was elected to City Council representing the Fourth Ward in 1917 and represented the Ward until 1923. He is listed in the Toledo City Journal dated 29 May 1922. Standing committees he served on included Public Improvements, Finance, Ways and Means, Gas and Light, Railroads, and Telegraph. He was also active on a committee to determine the appropriateness of a new city hall.

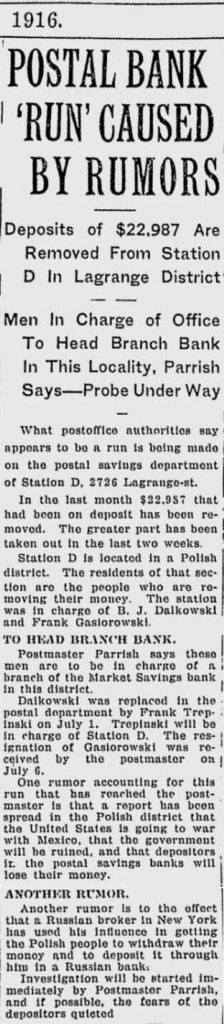

In early July 1916, the Toledo Market Savings Bank in the Polish District postal office experienced a run by its savings depositors withdrawing nearly $22,000 in a matter of a few days. This run was likely started by rumors that the US would go to war with Mexico and the US government would be ruined and that a Russian broker located in New York used his influence to get Polish people to deposit their money in a Russian bank. Dalkowski and Frank Gasiorowski were in charge of the post office in the Polish district (LaGrinka, this station was located at 2726 Lagrange St.) and were put in place to take charge of the Market Savings bank in the office. Postal banking existed in the US from about 1911 to 1966 and was central to our banking system. It was an alternative to the federal deposit insurance until 1933. This system was designed to prevent runs during turbulent times in our nation’s banks–they performed central banking functions before the Federal Reserve took on this task. Postal banking helped fund two world wars and reduced a massive government deficient after the Great Depression. So a run at this amount, which was great for 1916, $22,000 in 2022 would be equal to nearly $600,000. Toledo was tenth in the nation for the amount of deposits in these postal Market Savings banks. In an article from the American Economic Review, March 1917 authored by E.W. Kemmerer, these postal banks in Toledo had $3.40 deposited in them for each of Toledo’s 184,000 residents. So that $22,000 from one location was considered substantial. Dalkowski and Gasiorowski were put in place in order to manage and stop a fast run on deposits based on rumor.

In 1923, Dalkowski was asked to act as in the capacity of a parole officer for Frank Kalane. Kalane, who was only 28 years old in 1923, was found guilty of murder in 1914 in Canton, Ohio and given a life sentence. Kalane’s sister, Mary Lewandowski resided in Toledo and was widowed with seven children. Governor Donahey ordered Kalane to be released from prison to to abstain from liquor and to report monthly to Dalkowski.

Boleslaus later jointed Ohio Savings Bank, where he remained 16 years until the bank ceased to operate. During World War I, he participated in and headed Liberty Loan drives and was president of the Polish Citizens League. He also recruited young Polish men rejected from the service in the US serve in France. Boleslaus was civic-minded and established Wilson Park to provide the children in his neighborhood a safe place to play.

Given the history I was able to find on Boleslaus Dalkowski, I’m bewildered why A. A. Paryski so vehemently battled politically with him in their early lives, and so publicly in the Ameryka Echo. I have no connection personally to Dalkowski. I only came to know his existence when discovering his grave in Calvary Cemetery and reading the inscription on the stone–“He lived for service to his people.” He seems to have serviced his people well.

He died 18 December 1941. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery with his wife, Bronislawa.