1919: Strike and a Riot

Many Toledoans likely are aware of the 1934 Auto-Lite Strike. I’m not certain many are aware of another major labor dispute that preceded it in Toledo. That dispute began on May 5, 1919 and involved workers both at Overland and Auto-Lite plants. The dispute arose as the nation was winding down from war time production after World War I and was converting back to meeting a growing consumer demand for automobiles in the US and as the US Army was reducing its troops and soldiers were looking for jobs upon returning home.

This is not a short story. However, it is a vital piece of history to Toledo and it did affect many Polish Americans in Toledo because two Poles were killed and several more wounded. Overland and Auto-Lite were large employers in Toledo and many workers were immigrants or first generation Polish Americans.

John Willys bought the popular Overland brand in in 1907. In 1909, Willys acquired the Marion Motor Car Co. He then bought a factory in Toledo, the Pope Motor Car Co., which recently went bankrupt. Again, in 1914, he had made another acquisition in Toledo, the Electric Auto-Lite Company. By 1915, he was building a seven story headquarters in Toledo. In 1917, he formed the Willys Corporation to act as a holding company.

By 1920, he was employing about a third of the city of Toledo’s workforce. Overland’s growth was swift.

Let’s back up a bit now to 1919. Workers wanted to bargain for a 44 or 45 hour work week and standard wages. Overland proposed to its workers a reserve, or efficiency fund, as a type of profit-sharing. Funds were to be distributed quarterly to all employees who were on the payroll as of 18 December 1918. Soldiers who were previously employed would be considered as long as they made an applicable for re-employment soon after discharge. There was a plan also for future employees based on permanency and personal efficiency. Employees who had been employed six months or longer would become eligible to participate. A schedule of payrates was also proposed along with a 48 hour work week of shifts of eight hours, 35 minutes plus a five hour shift on Saturdays. The First Vice President of Overland, C.A. Earl claimed this was “competitive” as many plants in Toledo and Detroit were standardized on 55 hour weeks.

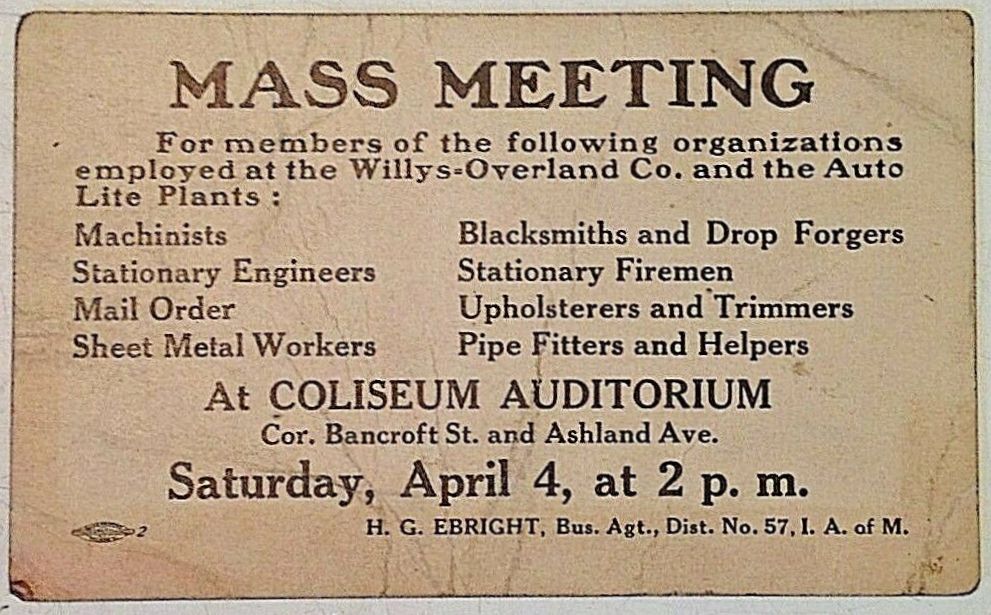

Workers called for and organized a mass meeting for employees of Overland and Auto-Lite on 4 April. Just over a month later, on 5 May, workers rejected the proposal from Overland for 48-hour work weeks and announced that at 3:30 the next day, a Tuesday, they would drop their tools and walk off the jobs. The 3:30 time was 36 minutes earlier than the normal quitting time of 4:06 p.m. Overland and Auto-Lite officials struck back by posting that men quitting work at 3:30 rather than 4:06 would be “pulled”—they would be paid off and the workers would lose their jobs. A last minute meeting between Overland officials and workers failed.

On Tuesday, 6 May, a lockout occurred. 9,500 Overland workers met at Terminal Auditorium and were instructed to do no violence, stay away from saloons, and to discourage any sympathetic strikes. Plant gates were locked. About 800 Auto-Lite employees also quit—they had time cards pulled that Tuesday morning. On 8 May, Mayor Cornell Schreiber made a statement that he was temporarily adding to the Toledo City Police Force by adding 100 citizen “soldier-police” who would do patrol duty in residential areas However, these citizen police seemed to provoke the strikers—these “soldier police” wore a uniform. At this point, the Toledo News Bee estimated about 10,000 workers had left work. Union leaders also warned that any union member caught participating in violence would be expelled. Picketers were given numbered badges to identify themselves.

Friday, 9 May, The News Bee was reporting that 16,700 workers were off the job. The strike now included the Toledo Ford Plant. The afternoon and evening before, riots occurred at the factory and the Overland plant and cars were stoned. Guards, policemen, and workmen were hurt but not seriously. Shots were fired by deputy sheriffs at the Ford plant. Some workers learned that local grocers refused them credit and several union leaders were forced out of their rented homes by the owners. The union men claimed the riot was incited by attempted violence by guards and patrolmen. Governor Cox ordered a mediator to Toledo to help negotiate the dispute.

Two weeks later, the Overland and Auto-Lite plants reopened on Monday 26 May. But picketing continued by union members. Particularly, the Blacksmiths and Dropforgers union continued to press the matter as the presence of a non-union dropforger was on site, with a claim that he was there to prevent fires within the plant. The union argued that by hiring the non-union man, Overland was breaking its faith with the union. However, union firemen and engineers were remaining at work as they were in a slightly different category than most workers. They carried state licenses and were members of other unions. The union dropforgers were working with consent of the other unions involved. The hiring of a non-union dropforger inflammed the situation. That same day, 26 May, Overland refused to make an estimate of the number of employees at work until Wednesday, 28 May. The plan was to open 56 departments on Monday, 12 on Tuesday, and 15 on Wednesday.

By 3 June, tensions were very high. A crowd was forming at the railroad crossing at Central Ave. Some coal was thrown at the factory windows. Picketers remained protesting; and other workers kept trying to get into the plant. A few men with “dinner buckets” (probably something similar to a lunch box today) were stopped and detained by the picketers, peacefully it seems with no violence. The picketers were attempting to convince the workers not to enter the plant.

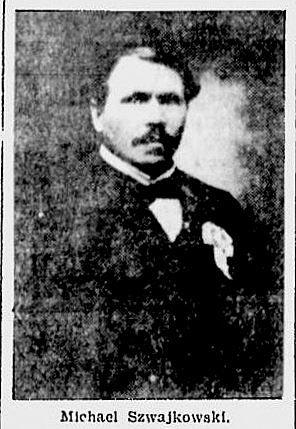

That evening, night riots erupted. A crowd gathered at the intersection of Lagrange and Everett. A “soldier-police,” W. E. Bristol, was walking along the area. He reported being chased by the crowed into the No. 14 Fire Engine House. From there, he called for reinforcements. Per Captain Leonard Spach, the commanding officer, the police did not fire until bricks and dirt were thrown at them. Two men were killed: Michael Szwajkowski and Stanley Balcerzak. Many more were injured.

I’ll get back to those killed and the injured in a bit—as this is a situation that involved Boleslaus Dalkowski. But first, let’s look at the reactions from the city, the unions, and Overland and Auto-Lite.

Mayor Schreiber in a statement to the News Bee on 4 June:

“I regret more than I can say that anybody had to be killed in the affair of yesterday and last night. It was necessary for the soldier-policemen to use their guns, it was the only was to disperse the mob.

I have done everything that I can. I have requested the governor of the state to send troops, but as yet have received no answer. Every deputy and all police we can get have been sworn in.

Order will be maintained in Toledo at any cost.”

The union leaders issued a response the following morning:

“Vice-President Earl’s conscience as forced him, as a matter of self-defense, to accuse laborers of being responsible for the present disorders.

If the present disorders are the result of the lockout at the Overland plant, then those responsible for the lockout are to blame. The Overland Company on the morning of May 6, locked out their employees after labor leaders the previous day had pleaded with them to continue to operate the plant under the conditions in effect prior to this date, and to negotiate with a committee elected by the employees on the proposed changes.

This they refused to do and arbitrarily locked out their employees. They have invited disorder by employing gunmen and strikebreakers as well as many workers under false impression as to the actual conditions.

The union pickets have done more to prevent disorder at all times than any other body of citizens and the regular police force has been open in its praise of the aid received from that source.”

It is not fully clear to me what source the unions are referring to: the picketers OR the “soldier-police” but given the context, I believe the union representative being quoted believed the “soldier-police” were openly praised and were receiving aid from the city police, rather than the union pickets being praised and receiving aid from city policy.

Additionally, Business Agent Quinlivan of the Central Labor Union issued a statement to address strikebreakers who had been witnessed entering the plant for work. That statement in part read:

“Mr. Earl, who seeks in his statement to place the blood of the soldiers’ victims on union officials appears to be bothered by his own conscience.

As we have substantiated by affidavits, Earl and his officials have been hiring strikebreakers for the past two weeks, paying their transportation, meals, and housing in the barracks at the Overland Plant.”

Overland officials made a statement denying that there were no New York workers brought into the plant to work at $1.10 per hour. There were reports that claimed New York workers were offered $14 and fares back to New York for a week’s labor. Overland then printed a “Preliminary Application for Employment” which it stated all new employees must sign. In part, this agreement had an applicant certify that he was agreeable to working a 48-hour week of 8 hours, 36 minutes for five days and then 5 hours on Saturday with overtime at time and a half after the established working hours. It also required the applicant to certify he was aware that there was a strike at Willys-Overland where men had demanded 44 or 45 hour workweeks and had other demands and that the applicant understood that resulted in 5,000 our of 13,000 men walking out. The applicant then was required to sign that he was agreeable to working on these terms and in accepting the job, he was not doing so as a strikebreaker but as a worker seeking regular permanent employment.

The plants remained closed after the riots and a federal judge, John Killits, was asked to order the plant to operate. Summons to 44 individuals were served for testimony. A restraining order was issued to limit picketing as well. The court ordered that there may only be 150 pickets, with no more than 20 on duty at any given time. Workers asked for 220 pickets. Additionally, picketing was limited to 6 am to 6 pm and records maintained of pickets so that the courts could demand them as needed.

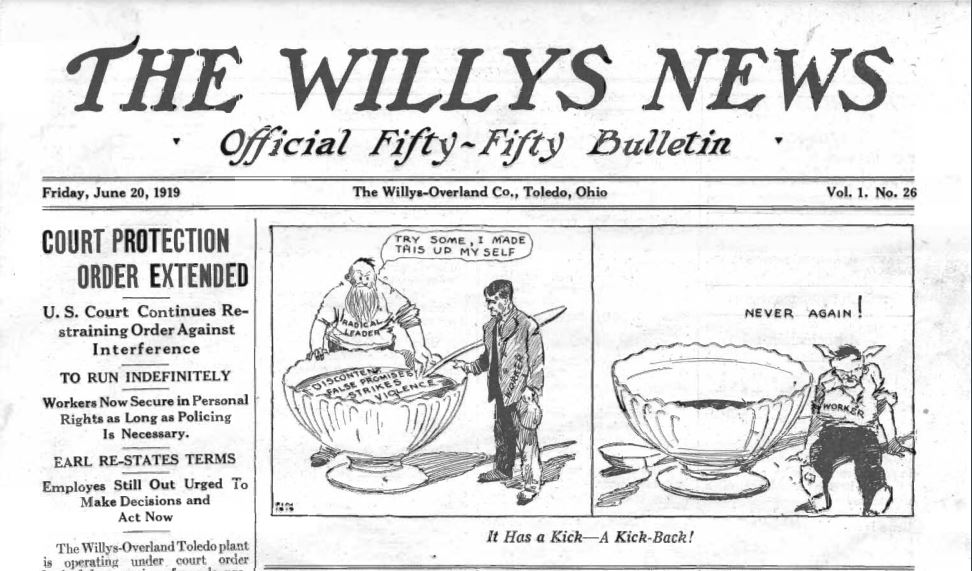

Auto-Lite re-opened Wednesday 11 June, Overland on Friday 13 June. On Friday 20 June, the Willys News, Official Fifty-Fifty Bulletin announced that court protection order was extended, would run indefinitely and that workers were secure in their personal rights as long as policing was necessary.

However, Overland through its Willys News, Official Fifty-Fifty Bulletin, reinforced some negative press that the unions were receiving in the local news. The local news was claiming that the labor strike was a “Bolshevik” movement and would infer it was somehow related to the I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World, a union founded in part by Eugene Debs and Mother Jones. This union was founded on the idea that workers were exploited by and are in economic struggle with the employing class.) The reality of the unions involved in the Overland and Auto-Lite strikes in 1919 was not related to the I.W.W. The American Federation of Labor was operating with all unions involved in this strike (there were several, but the AFL operated as a single entity to negotiate on behalf of all the involved unions and their members). An example of the way Overland let its employees know how it felt was a cartoon published in the 20 June issue of the bulletin.

Now to return to the victims of the riot—those who died and those who were injured.

Michael Szwajkowski was fatally shot in the 4 June riot. He was the father-in-law of Boleslaus Dalkowski. Dalkowski himself issued a statement immediately after the riot in which he stated

“…it is absolutely false that the policemen fired in self-defense. I was coming home from a committee meeting at City Hall and saw the crowd at the engine house. It was a quiet, orderly crowd… Some of the young fellows yelled, ‘Shoot you cowards, shoot!’ The policemen went into the engine house and began to shoot… straight across the street at innocent people.”

Besides his daughter, Bronislawa Dalkowski, Michael Szwajkowski was survived by his wife and four sons. He was 75 years old at the time of his death.

The other man killed in the riot was Stanley Balcerzak. Stanley was 24 years old and resided on Pearl Street. He was discharged from the army only months prior to his death and worked at the Auto-Lite plant on Champlain Street and the morning of the riot, he began a new job at another plant. Stanley was survived by his parents, five brothers, and three sisters.

John Modrowski, a former policeman who was employed as a molder at the time of the riot while standing across the street from his home, witnessing the riot. John was shot by four bullets in the right leg. His leg was was shattered and amputation was necessary. John was fortunate. His brother, Martin, was a fireman at the No. 14 Engine House and rushed over to his aid by tying a rope to his leg to stop the flow of blood. Martin then carried him to a doctor.

Other Polish Americans injured in this riot were William Pavlowski of Maplewood Ave., Milton Tomajewski of E. Delaware Ave., Joseph Jastrezemski of Mettler St., George Gotozewski of Mettler St., Chester Przybyz of Delker St., and Chester Bridcinski of Delker St.

A. A. Parynski, never without a bit of controversy surrounding him (even when he didn’t ask for it!) was involved in this situation to a small extent. A delegation of men who were angry at editorials Paryski printed in the Ameryka Echo voiced their indignation at the entrance of Paryski’s printing plant on Nebraska Ave. Paryski stated the gathering was one of several of his personal enemies.